What are Springs-Dependent Species?

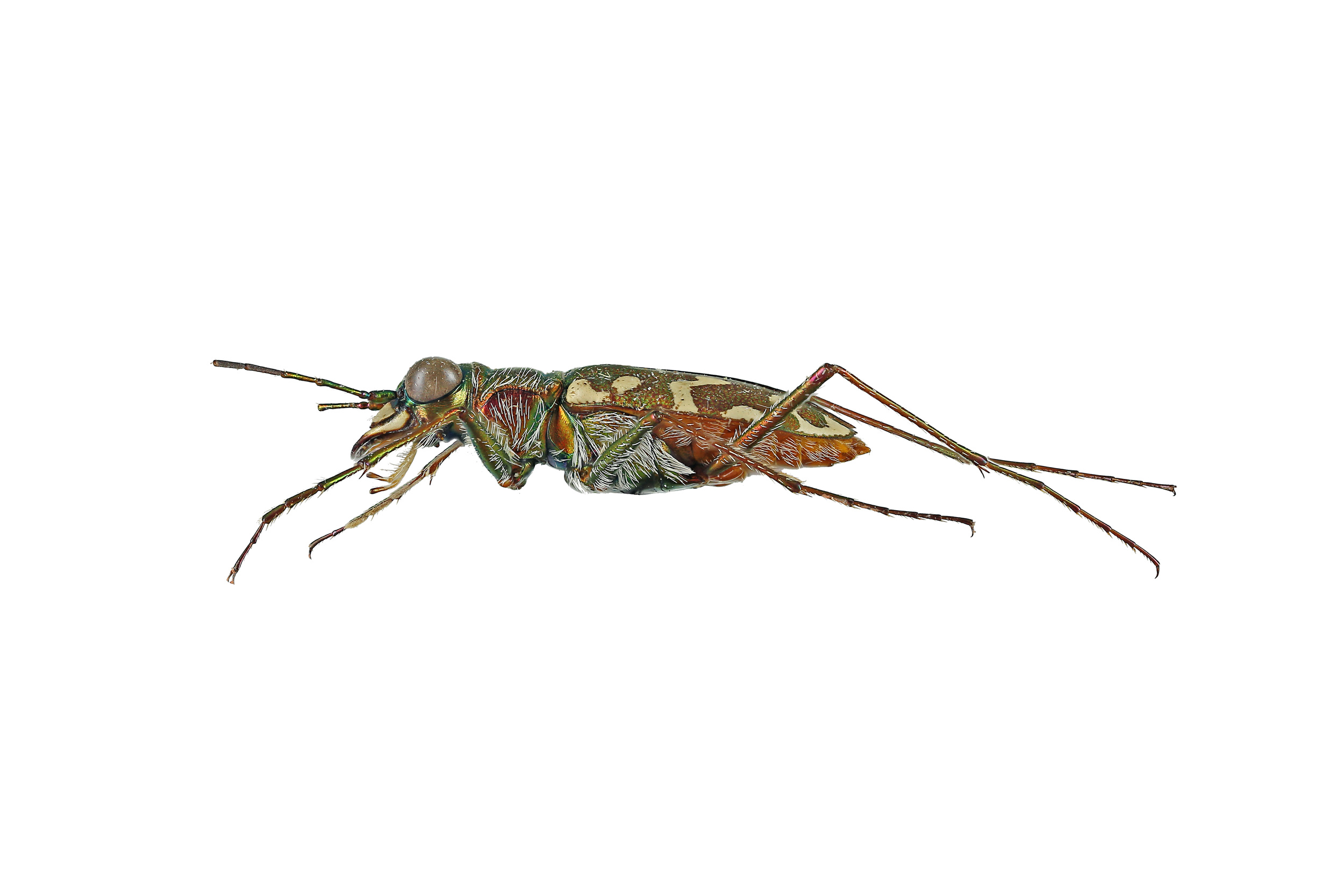

In arid, mesic, and subaqueous (underwater) settings alike, springs are renowned as hotspots of biological diversity. Springs are places where life is highly concentrated and the species occurring at springs include upland, riparian, wetland, and aquatic taxa, some of which exist only at springs. These springs-dependent species (SDS) are organisms that require springs habitat for at least one life stage. Some SDSs, such as many hydrobiid springsnails (more than 150 species in North America) and desert pupfish (Cyprinodontidae) occur only in springs sources and outflows, while some dragonflies, aquatic true bugs, tiger and diving beetles, crane and shore flies, amphibians, fish, and other vertebrates require springs for spawning and/or larval rearing habitat, or for over-wintering (e.g., Florida manatees) or winter dormancy (e.g., some turtles). If a species cannot exist without springs habitat, we consider it to be springs dependent.

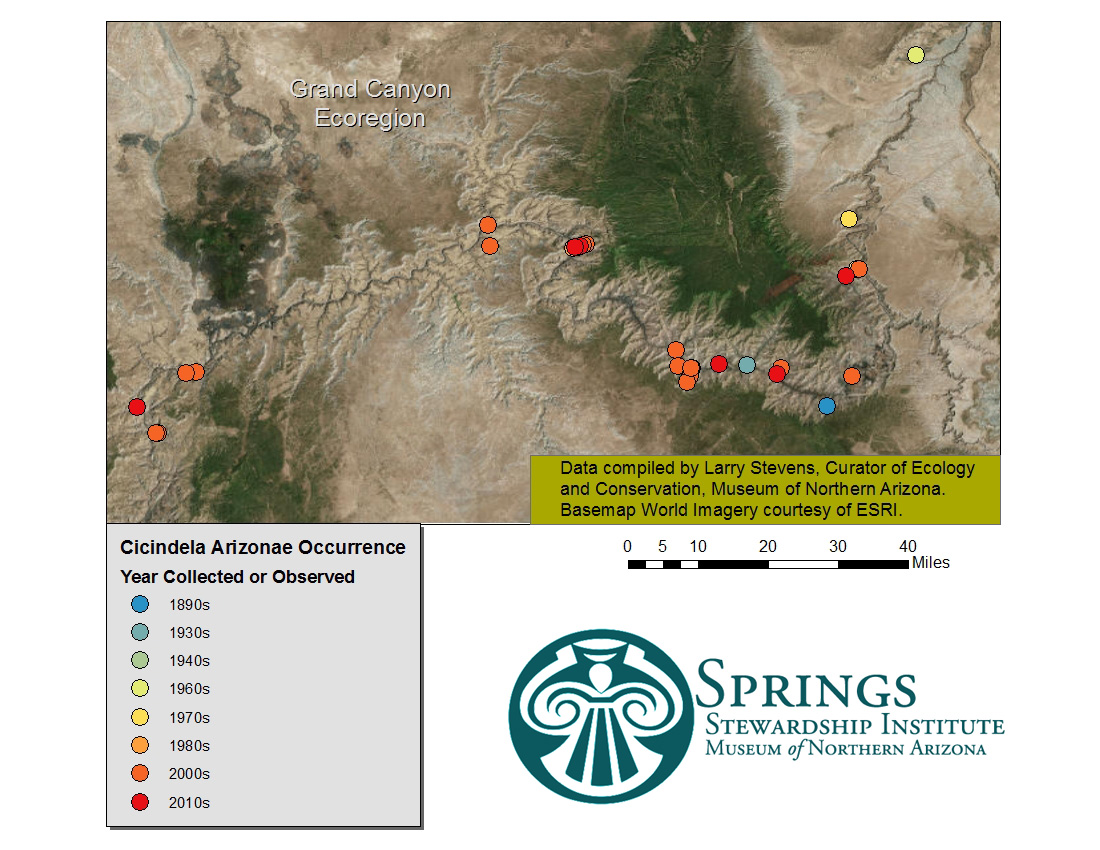

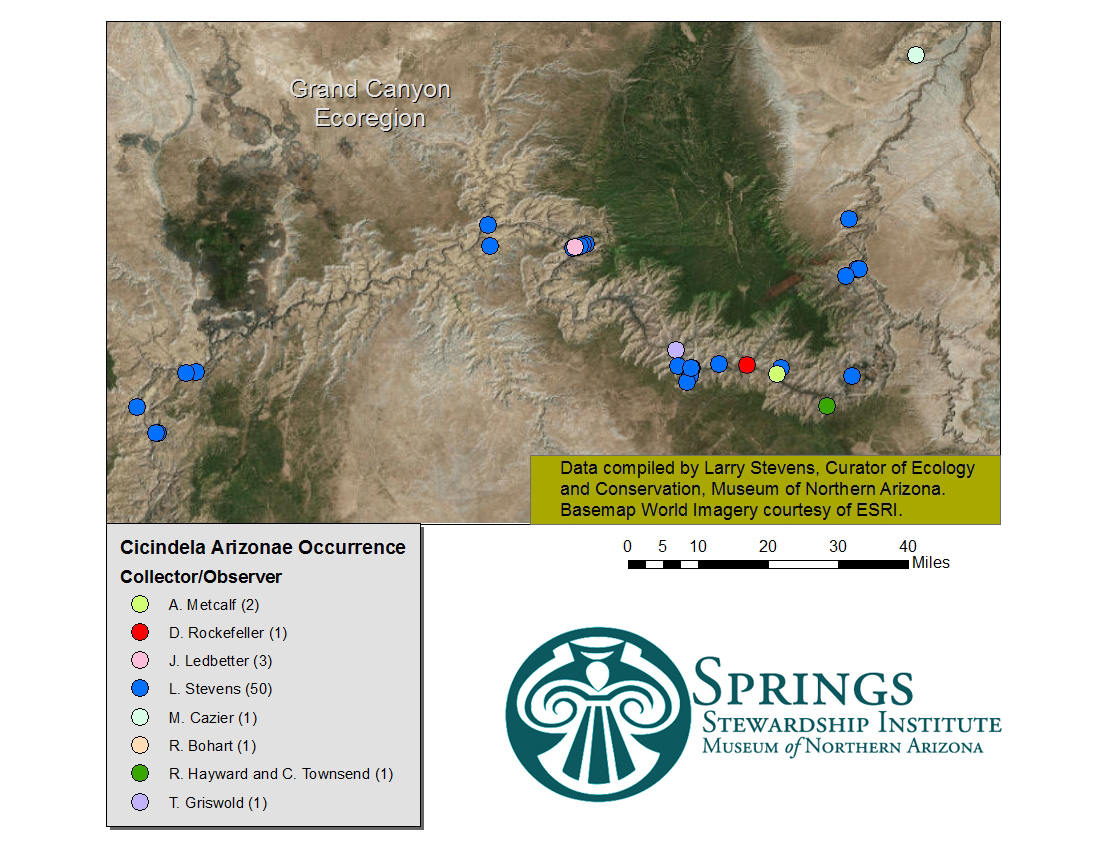

While springs are small habitats, making up < 0.01% of the land area of North America, they are extraordinarily rich in biodiversity. In our recent inventories in large National Forests, National Parks, and other public land units, we commonly encounter 20-25% of the regional plant species in visits to 50-75 springs, which may only occupy 3-5 ha (7-13 ac) of land. In addition, we find a host of aquatic and riparian invertebrate and vertebrate species that occur nowhere else in the landscape. Nationally, at least 10% of the federally listed threatened and endangered species are springs dependent, even though springs make up a tiny fraction of the national land area. In addition to those federally listed species, we have documented more than 1,000 SDS, most of which are not protected, but many of which are rare and exclusively found in just a few springs.

Therefore, springs are "Noah's ark" habitats, protecting much of our biodiversity and natural heritage for future generations in tiny, isolated habitats. But springs, as a fleet of arks, face stormy seas and an uncertain future because of unrelenting human demands and ignorance. We at SSI are hopeful that education will increase awareness and help calm that ocean of onslaught.

The Springs-Dependent Species project

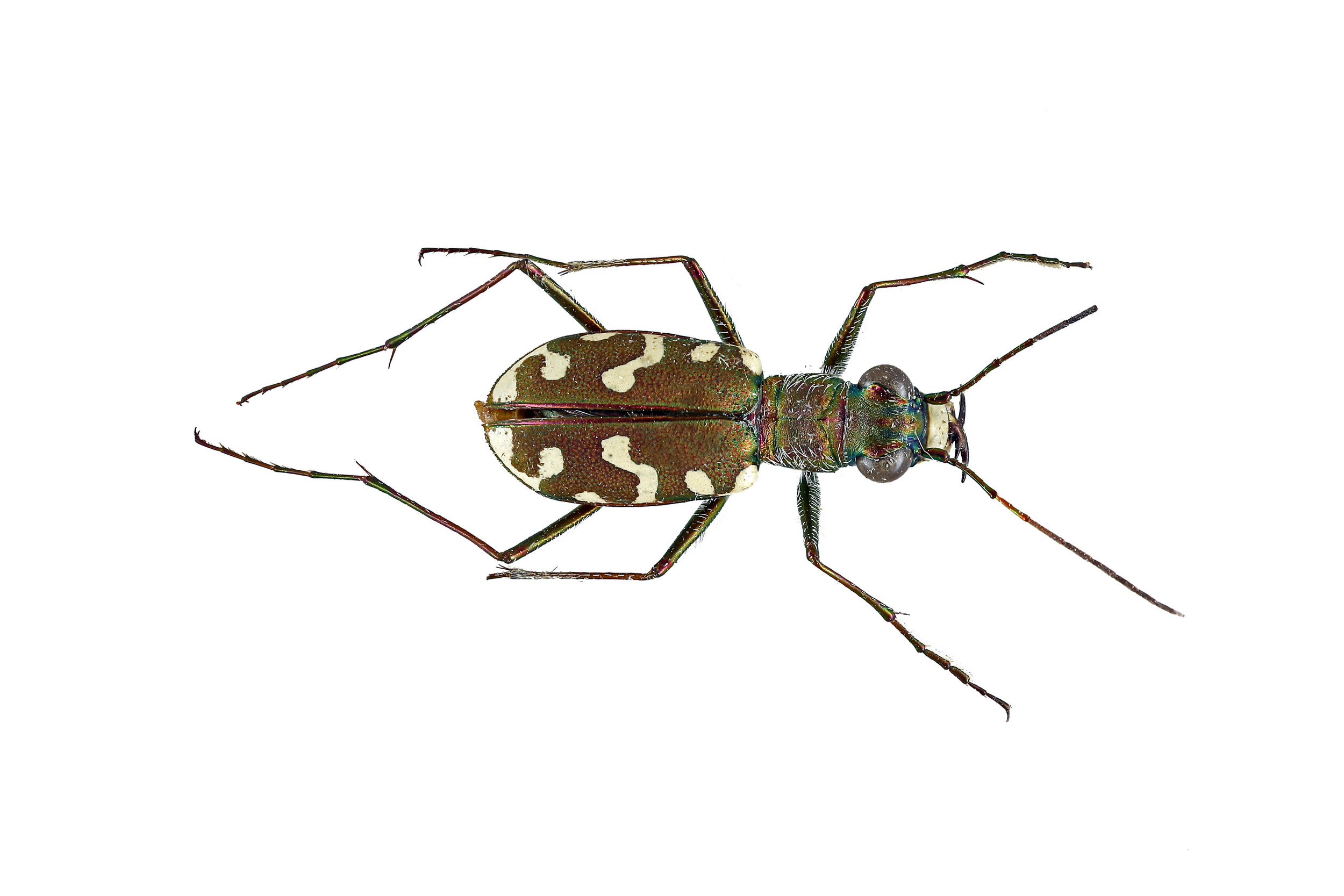

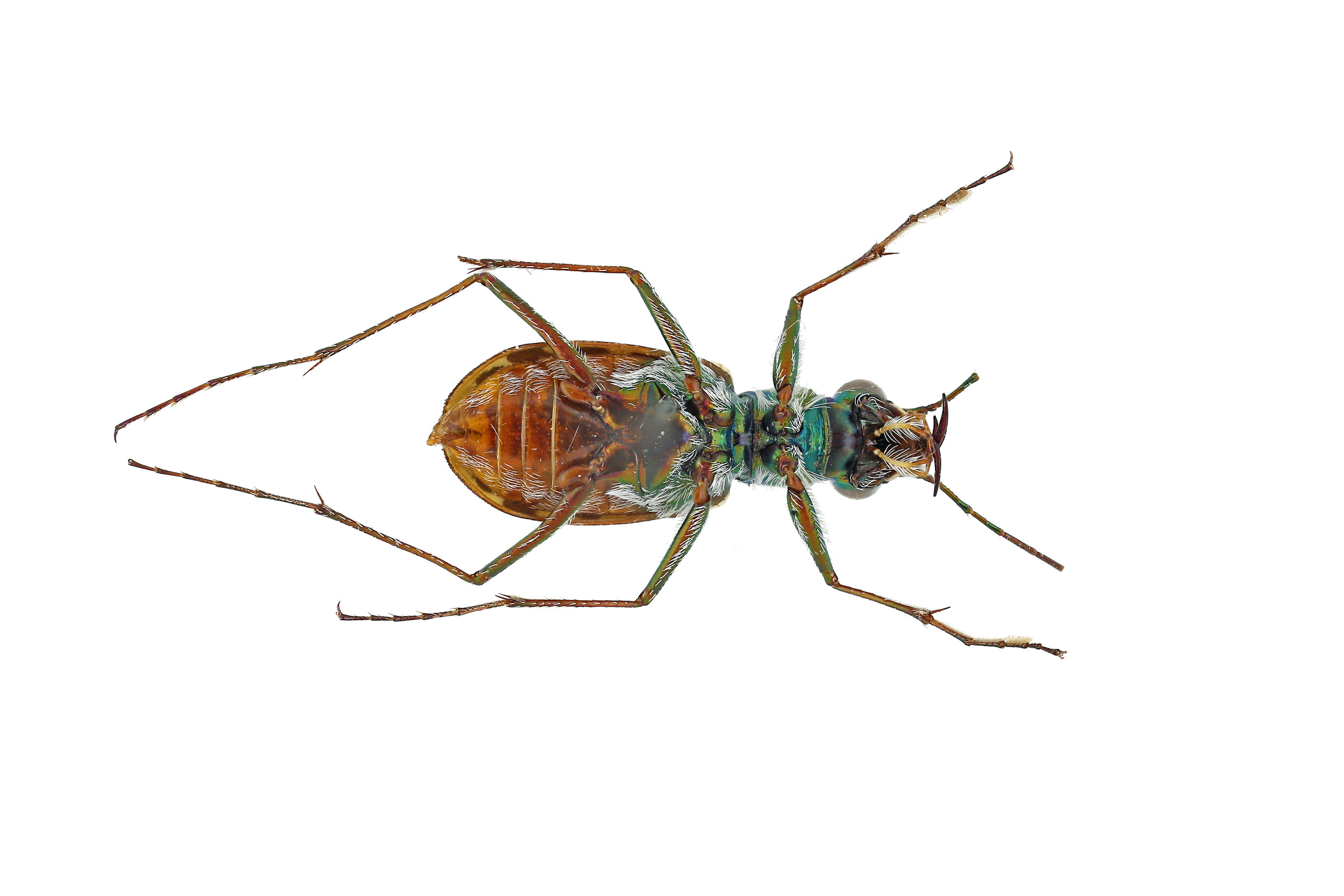

SSI, in collaboration with Dr. Gary Alpert, has begun work on the Springs-Dependent Species (SDS) Online Directory. The project, started in April 2015, aims to bring attention to endemic and endangered species as part of our effort to increase awareness and improve stewardship of these vital freshwater resources.

Each species in the directory has complete taxonomic information as well as maps of their geographic distribution and high-resolution images. The images are taken in our laboratory at the Museum of Northern Arizona using a Canon 6D DSLR mounted to a StackShot focusing rail. Specimens are placed in an imaging box lit with LED array lights to illuminate every detail. The system then takes 30-50 stacked source images that are edited in Helicon Focus.

Contributing to the project...

SSI has the capabilities and a highly-trained staff to publish articles on Springs-Dependent Species. However, we require additional funding to take this project to the next level. If you would like to play a role in advancing education of springs ecosystems and their dependent species, please donate to our General Fund. Donations are tax-deductible and can go a long way towards achieving our mission.